The Intercept

Aug. 12, 2022

Should a military veteran who has been reliably accused of war crimes, and who admitted that he killed a prisoner, be invited to train police officers on how to do their job?

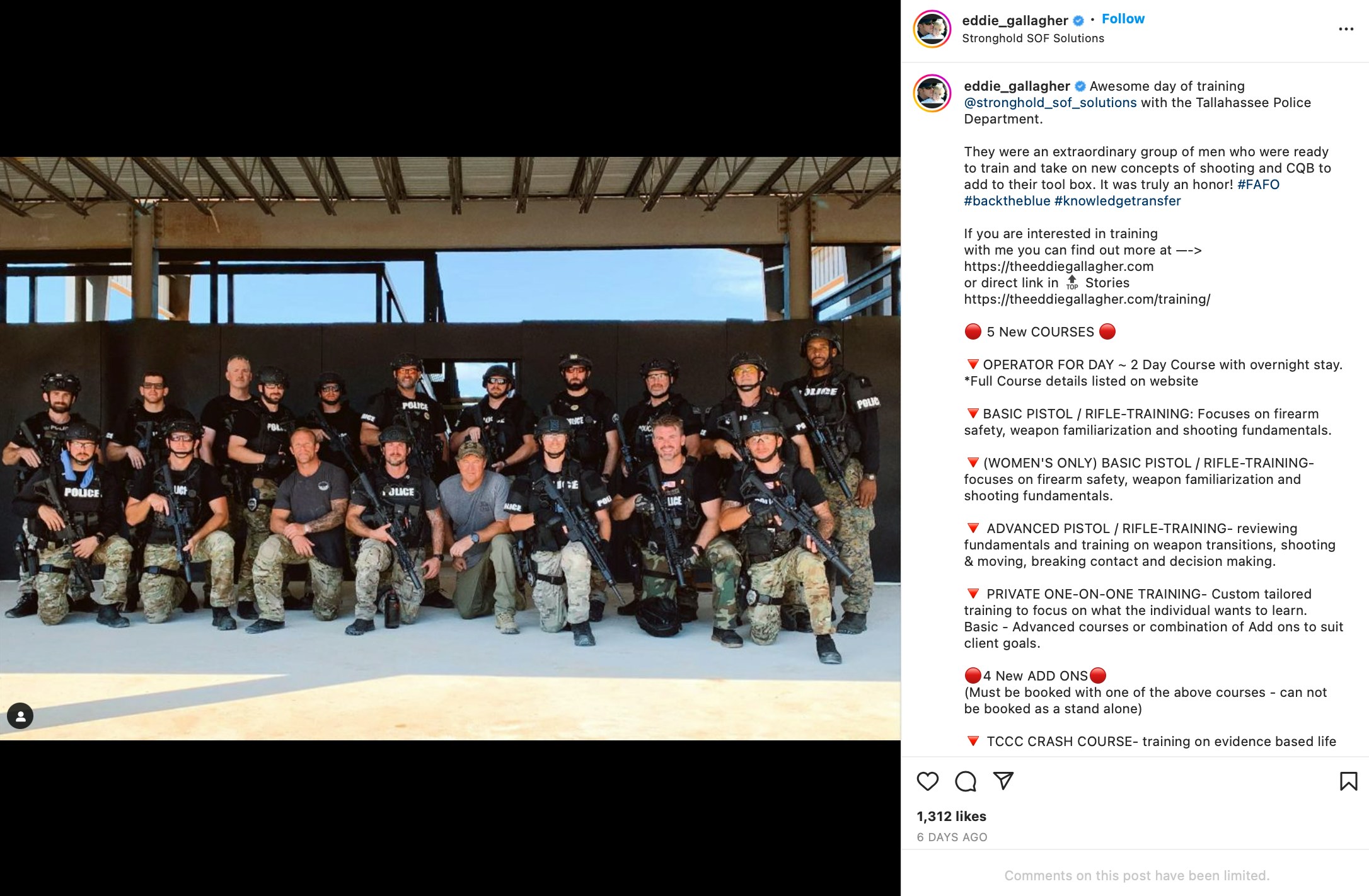

The police department in Tallahassee, Florida, found a surprising answer to that question. Retired Navy SEAL Eddie Gallagher, accused by his fellow operators of intentionally shooting civilians and murdering a prisoner in Iraq, shared a photo and video on Instagram last week in which he described working with Tallahassee police officers in close-quarters combat and other lethal skills. He posted a picture of himself flanked by the rifle-bearing officers in Florida, with his caption describing an “awesome day of training” with “an extraordinary group of men who were ready to train and take on new concepts of shooting and CQB to add to their tool box. It was truly an honor!”

After Gallagher’s picture was spotted and shared by journalist Wesley Morgan, the Tallahassee Police Department stumbled forward with a believe-it-or-not statement that its officers were merely practicing at a private facility operated by a company called Stronghold SOF Solutions, which Gallagher is affiliated with. Gallagher happened to be at the facility and offered his “input” to the officers, according to the TPD. The department did not provide an explanation of how or why its officers assembled for a group photo with Gallagher, whose current business endeavors include private instruction on weapons and tactics.

Gallagher, imprisoned before his court-martial in 2019, is a free man because a military jury controversially declared him not guilty of premeditated murder, and his conviction on just one minor count — of posing in a picture with a dead prisoner — was essentially overturned when former President Donald Trump granted him clemency. Not long after the trial and grant of clemency, the New York Times released a trove of evidence from Gallagher’s fellow operators that laid out their damning case against him.

The core problem here is not Gallagher or the Tallahassee Police Department. The conduct of each is consistent with a decadeslong meshing of the military and policing — a violent disaster in America. The process, explored in Radley Balko’s “Rise of the Warrior Cop,” began in the 1960s, was stepped up during the so-called war on drugs, and reached terminal velocity after 9/11, when vast amounts of funding and weapons were poured into local law enforcement agencies, which deployed these resources mainly against minority and poor communities. One of the most notorious signatures of this destructive process is the Pentagon’s 1033 program, which since 1990 has distributed more than $7.4 billion in military weapons — including armored vehicles, grenade launchers, and sniper rifles — to police departments across the country.

This deluge of military hardware among civilian populations is harmful enough, creating mini-armies inside American communities that are desperate for better schools and social services. But what’s been just as harmful, if not worse, is the military mindset instilled in police ranks after 9/11. As Arthur Rizer, a former police officer and military veteran, wrote recently, “We have for years told American police officers to regard every civilian encounter as potentially deadly, and that they must always be prepared to win that death match. … It was always obvious to me that military tactics, training and weaponry had little place in civilian policing.”

And that’s where “trainers” like Gallagher come into play.

In a post on Eddie Gallagher’s Instagram, members of the Tallahassee Police Department are seen with Gallagher for a training hosted by a company called Stronghold SOF Solutions at its facility in DeFuniak Springs, Fla.

On Killing

One of the most prominent and controversial police trainers these days is Dave Grossman, a retired military officer who catapulted onto the lecture circuit after writing a book titled “On Killing.” Our paths crossed in the early days of the 9/11 era, when I was working on a magazine story and attended a talk he delivered in 2002 to a military audience whom he saluted at the end. It was a boilerplate speech for him, delivered hundreds if not thousands of times since, in which he talked about the ways in which soldiers should be trained to kill so they do not hesitate to pull the trigger and do not feel guilty about it afterward. Even in the military community, his theories were controversial and disputed by academics who believed that Grossman did not fully understand the dynamics or history of killing in wartime.

Grossman was primarily speaking to military audiences in those days — there was a lot of demand for people like him as the Pentagon was beefing up its ranks and starting its catastrophic wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. After a while, as fewer U.S. soldiers were deployed overseas, he transitioned to speaking to a broader range of civilian groups, especially police departments, even though his base of experience is in combat psychology. His policing lectures are grafted from his military talks, emphasizing the danger of the job and the need for split-second aggression — even though policing is hardly the most dangerous profession in America. (Loggers, roofers, farmers, and sanitation engineers, among other workers, have higher on-the-job fatalities.) In a 2020 story on Grossman, the writer Justin Peters noted that “there is a cottage industry of trainers and consultants who encourage police to see their beats as a battlefield” and described Grossman as likening America to “a terrifying place where police are both the primary targets of and defenders against super-predation.”

Grossman, like Gallagher, is just a symptom of the problem.

In an encouraging development, Grossman’s lectures to police audiences are getting criticized more frequently than before. Last year, the Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police canceled a talk by him after justice advocates noted that his observations on police killings have included a remark that law enforcement officers can have the best sex of their lives after an on-the-job shooting. (A spokesperson for Grossman, asked for comment, told The Intercept via email, “The human body processes stress and a deadly force encounter many different ways. This is one way of MANY that humans react to and process what they just went through.”) A recent story by the Washington Post noted that the sorts of workshops conducted by Grossman and others were cited in a lawsuit over a police killing in Spokane Valley, Washington.

Yet Grossman, like Gallagher, is just a symptom of the problem. Even as the Tallahassee Police Department was trying to back away from its connection to an accused war criminal who has become a right-wing rock star in the fashion of Kyle Rittenhouse, local journalists unearthed a recruitment video from the department that highlighted an array of military-grade equipment and tactics used by its officers. The video showed off an armored personnel carrier, a camouflage-covered sniper, a squad of riot police marching in a V formation, and an armored bulldozer called the “Rook.” But don’t blame the TPD for being over-the-top: The gear in its video is standard in police departments across the country.

The fundamental problem, which was generations in the making and will perhaps be generations in the solving, is the internalization of a military force and a military ideology that were ostensibly built for external purposes. This is the forever wars coming home. The problem is not just that military spending since 9/11 has helped impoverish America while destroying foreign countries in illegal wars that cost trillions of dollars and left a million or more people dead (mostly foreigners, but plenty of Americans too). History has shown that the aftermath of foreign wars is not what you might expect. “War is not neatly contained in the space and time legitimated by the state,” noted Kathleen Belew in “Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America.” She added, “It reverberates in other terrains and lasts long past armistice. It comes home in ways bloody and unexpected.”

And we have just seen one of those ways: Eddie Gallagher giving shooting tips to cops.